Graffiti, especially on trains and subways, has been one of the most controversial forms of urban expression. While writers see it as a moving canvas, institutions perceive it as a challenge to authority and a logistical problem. But what happens when graffiti is documented from the perspective of those working to prevent it?

The book Scene of Crime offers a unique and fascinating point of view on graffiti on the Toronto subway, using images and documents produced by the security staff of the city’s Transit Commission. This unusual approach not only sheds light on the visual impact of graffiti, but also on the operational context, procedures, and attempts to control it. This approach offers a raw and revealing look at the impact of graffiti on urban infrastructure, seen through the eyes of those working to control it.

In this interview, we speak with Jamie Jelinski, the creator of Scene of Crime about how he has managed to transform official archives into a work that challenges traditional narratives of graffiti.

How did the idea of making a book from the point of view of subway security personnel come about?

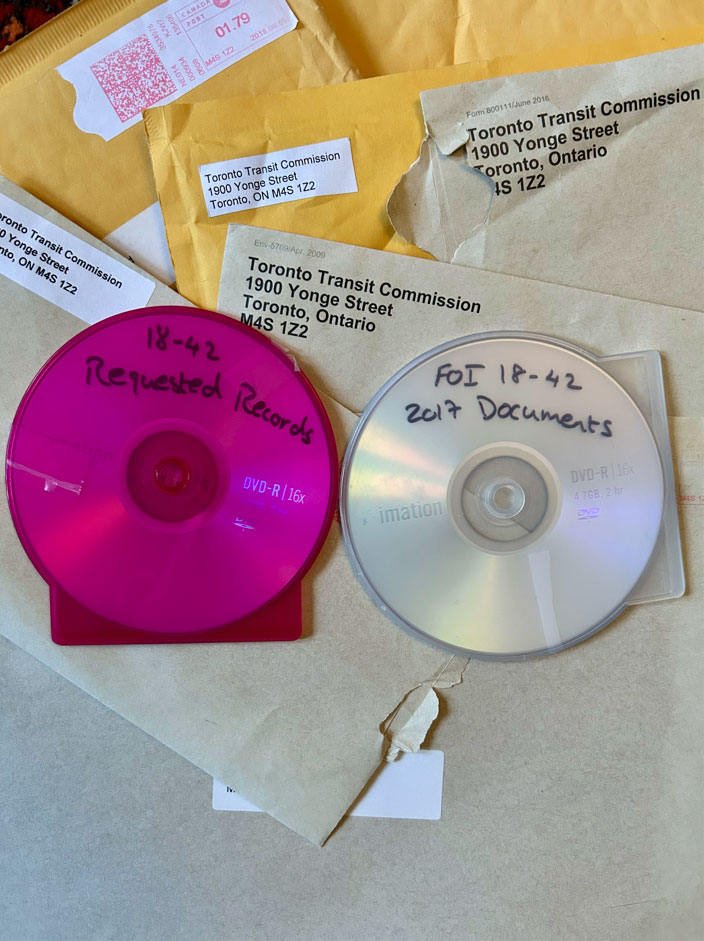

I work as an academic researcher, focusing on visual culture studies, which essentially means researching images. This has led me to explore how law enforcement creates and uses images—whether it’s drawings, photographs, sculptures, or other forms of visual media. Over the past five years, I’ve been developing methods for analyzing “unseen images,” or those that exist but aren’t easily accessible to the public or scholars like me. I’ve been using freedom of information (FOI) requests to access these materials from various law enforcement agencies. I’ve always had an interest in graffiti, so in 2019, I decided to file a request with the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) to see if I could access investigative photographs and incident reports related to graffiti on the Toronto subway system. That request was successful, and I continued filing follow-ups to get more recent material. For a while, I thought I’d use these materials exclusively in an academic book I’m working on called Unseen Images: Crime, Access to Information, and Visual Culture in Canada. But academic books are typically written for a very different audience, and their image quality is often poor. About two years ago, I had the idea of putting together a book using this archive, but it wasn’t until late 2023 that the project really gained momentum. Graphic designer Lorzenzo D’Ambra, who also co-authored Roma Subway Art (2021), was in Montreal and offered to help design the book. He also convinced me that there was a real audience for this type of publication. Now, about a year and a half later, it’s finally here.

Did you collaborate with security personnel or did you use existing material? Was there any resistance or difficulty in accessing these materials?

This wasn’t a collaboration in the traditional sense. I haven’t been in contact with any TTC security about the book, nor do I want to be. The incident reports they wrote offer more than enough insight into how they investigate and document transit graffiti. They’re not objective accounts, but they weren’t written with this project in mind, and they probably didn’t anticipate them being made public in this way. As for resistance, initially, there were few barriers to obtaining the material through FOI requests, which are made possible under Ontario’s Municipal Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (MFIPPA). For a $5 application fee, I had the materials in hand within a few weeks. However, things got more difficult when I started making follow-up requests for newer material and video surveillance footage mentioned in the reports. The TTC began making it harder to access, denying the existence of certain material or claiming it had been transferred to the police. After filing an appeal with the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario, the TTC finally located and provided the materials they had previously claimed didn’t exist. More recently, another request “got lost” on its way to them. I’m curious to see how this book affects future FOI requests, whether made by me or others.

What challenges did you face when working with documents that were created with an opposing perspective to that of the graffiti writers?

This wasn’t a challenge for me—it was one of the driving forces behind the project. Honestly, I don’t even see this as a “graffiti book.” From my perspective, it’s a book of investigative photography of transit graffiti. The “opposing perspective” is central to the book, and I leaned into it. I didn’t want to create another conventional graffiti book filled with high-quality images taken by graffiti writers at their best angles and with perfect lighting. Books like Chiaroscuro (2015) by my friend COKNEY, and Subterráneos (2018) by Enrique Escandell, which utilize police images inspirational. I see Scene of Crime as adding to the conversation in a similar way. The real challenge, unfortunately, was deciding what to include. The archive I was working with consisted of hundreds of incident reports and photographs over twelve years, from 2008 to 2020, and including everything would have made the book cost-prohibitive. So, I had to make choices about what to feature. I picked those that best represented the larger archive while also keeping the book engaging, both narratively and visually. Some reports were chosen for the compelling details they contained, even if the photos weren’t the best quality. Conversely, some reports were fairly ordinary, but the photos were unique or unconventional. I also wanted to include work by both local Toronto writers and tourtists for variety.

Have you had any initial feedback from writers or security personnel? Has any attempt been made to contact any of the artists whose works appear in the documents to get their reaction to the book?

As I mentioned, I haven’t been in contact with TTC security, nor am I particularly interested in their opinion on the book. What matters more to me is what they think about the graffiti they investigate on a near weekly basis. Whether they like the project or not is irrelevant. The TTC, as a publicly funded entity, has a legal obligation to disclose this material, and anyone who requests it, including me, is free to use it as they see fit. As for writers, I’ve had minimal contact with them, beyond the three commissioned essays by Causr, Euroboi, and Liv. That’s by design. Just as I wouldn’t want TTC personnel influencing the book, I didn’t want any input from the other side of the spectrum either. I want the readers to experience the content without external interference. That said, I’m sure there will be mixed reactions—both positive and negative—and I’m fine with that.

Do you think that writers might consider this book a form of recognition, even if it comes from an unexpected source?

I think some writers will appreciate that their work is featured in the book, while others might not be as thrilled. I wrote about this in the introduction. Personally, I believe once a piece is painted, the writer loses control over how it’s consumed, whether they share their own photos of it or not. If someone feels recognized by having their work included, I’m happy to have contributed to that feeling, but it was never my intention. My focus was always on the ways the TTC and its security investigate, document, and archive graffiti. In that sense, I consider transit security to be the primary—even if unintentional—audience for this graffiti. They’re the ones who first interact with the work, document it, and make sure these digital images exist long after the graffiti itself is removed. To me, that’s a more lasting form of recognition than anything my book could provide.

Are there any specific cases, incidents or writers that repeatedly stand out in these archives?

In the book’s introduction, I describe an incident from the spring of 2020 at a popular subway layup in Toronto. Three people showed up to paint, but they were interrupted by four others who came to do the same. What I find fascinating about this case is how well-documented it is across multiple mediums—incident reports, photos, and video surveillance. Comparing the security’s written account with the surveillance footage, I noticed they didn’t even bother watching the whole video because their version of events didn’t line up with what actually happened in the footage. This type of discrepancy is crucial because these reports are meant to be objective documentation, but they’re clearly open to interpretation.

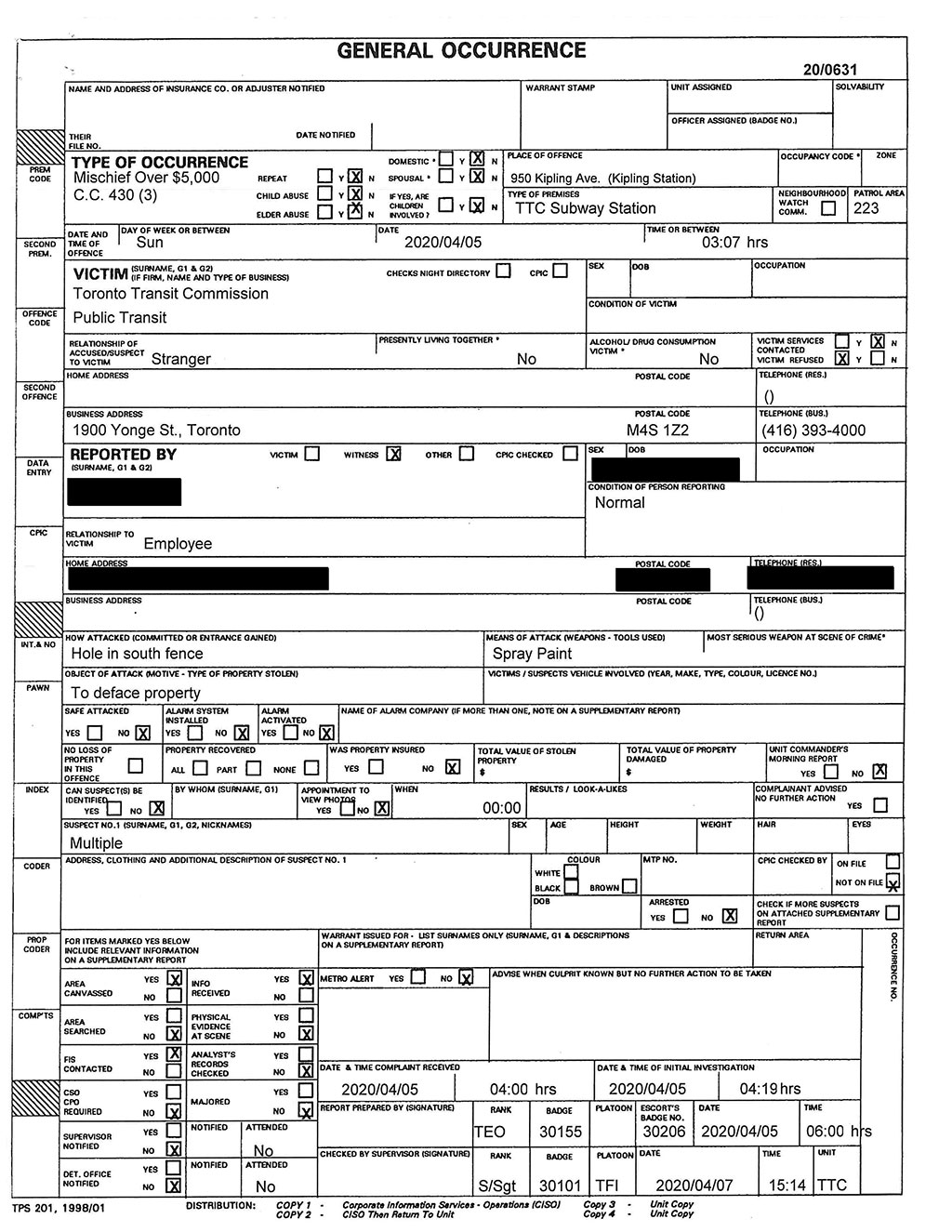

Another interesting thing I point out in the book’s introduction is the fluctuating damage estimates. For example, in 2020, removing four pieces from the side of a train was valued at $1500, but just two months later, the removal of two pieces was estimated at $2000. Then, a few weeks after that, the cost for a single piece went up to $2000. There’s no consistency in these numbers, and I think it’s important to highlight, especially since writers can be held financially liable for these damages. The book also includes some great chase stories, but for those, you’ll have to check out the book itself.

Do you think this book could inspire others to document graffiti from unusual perspectives?

I hope so. At the very least, I hope it encourages people—whether they’re writers, authorities, or graffiti fans—to think about transit graffiti in new ways. Scene of Crime reveals the whole bureaucratic process behind subway graffiti, an aspect that hasn’t been given much attention, even though it plays a huge role in how graffiti is managed and consumed. Graffiti is typically tied to the actions of the writers, but the other side of the story—the security, the documentation, the archiving—is just as crucial. If I did my job right, this book should open people’s eyes to that.

Will the profits from the sale of the books be shared with the subway company?

There’s very little profit to be made from a project like this. Producing a high-quality, hardcover photo book locally in small quantities is expensive. There might be a modest profit after covering production costs, but that wasn’t the goal of the project. The purpose was to offer a unique perspective on graffiti, something people haven’t seen before. But to answer your question, even if there were profits, there’s no way I would share them with the TTC. Given how they’ve actively tried to block the disclosure of the materials included in the book, they’re hardly entitled to any part of the proceeds, which would roughly amount to handful of subway rider’s fares anyways.

Would you like to explore other contexts or cities to do similar projects?

Most of my research, including projects outside graffiti, focuses on the Canadian context. While I might consider doing something similar for cities like Montreal or Vancouver, I don’t want to simply repeat what I’ve done here. I have some ideas for how a similar book could be approached differently, but I want to see how this one is received before committing to another project like it. I’m also working on a few non-graffiti-related projects, so I have to balance my time. But, I’d definitely like to work on something comparable in the near future.

Remember that you can get your copy HERE.